Most of the tourists who visit Zanzibar do not know much about the horrendous genocide that occurred on these exotic beaches in January 1964. If Bomi Bulsara and his family had failed to flee to England that year, the world would have probably never known Freddie Mercury.

It’s Saturday, January 12th. While we are waiting to enter one of the national parks in Zanzibar, I join a group of locals on a terrace of a bar who are intently watching a live broadcast of something that can be only described as a parade/celebration. It’s the Revolution Day in Zanzibar and this year, the celebration takes place on the Pemba Island which, in addition to Unguja (often called Zanzibar) and several smaller islands, makes the Zanzibar archipelago. The people at the stadium have formed a number 55 with their bodies, marking the 55th anniversary of the Zanzibar revolution which took place on January 12th, 1964, the day when Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah was overthrown.

Several months later, the Zanzibar archipelago united with Tanganyika in the continental Africa and a new state emerged, which name – Tanzania – was an abbreviation of the two territories’ names. On the surface, this looks just like any other revolution day, but this revolution was somewhat special – not only due to the fact that, during it, dozens of thousands of Arabs and Hindus were murdered and expelled out of the country, but also because this is the only genocide in the history that was entirely filmed as it was going on. A crew of Italian documentary filmmakers happened to be around, filming the movie called ‘Africa Addio’. First, the film shows never-ending lines of Arab civilians walking in between palm trees. They resemble a giant white snake. Only when the crew’s helicopter gets closer, we see that the civilians are guarded by black soldiers. Later on, they are split into the groups of 100 and sent into the earlier dug out holes in the ground in which they fall after being killed.

Second, even more dramatic scene, is taking place on the beach. Civilians – men, women and children – are running towards the sea, some manage to swim, some board overcrowded shipwrecked vessels, all trying to escape certain death. A day later, the Indian Ocean washes their bodies ashore.

All of this, to the minute detail, was recorded on film. You can see the selected scenes from ‘Africa Addio’ on YouTube, in the clip called “Arab Massacre in Zanzibar”. A descendant of one of the surviving Arabs uploaded the video.

THE MUSICAL CHILD OF BOMI BULSARA

What actually happened? In short, the history of the Zanzibar Archipelago is as follows: seven years after Columbus’ “discovery” of America, the Portuguese Vasco da Gama landed on the island in 1499 which remained under the Portuguese rule until the late 17th century. In 1698, Zanzibar was occupied by the Arabs from Oman who ruled sovereign until 1890 when the archipelago became a protectorate of the Great Britain but the Arabian sultan remained in power with a certain degree of autonomy. It is interesting to note that the Oman sultan moved the seat of his dynasty from Muscat in Oman to Zanzibar, thousands of miles away, in 1840. Something similar happened when the Portuguese royal family fled to Brazil in 1807, running away from Napoleon.

History records show that Zanzibar had one of the shortest wars ever – the 1896 rebellion ended with the Sultan capitulating 45 minutes after Stone Town was attacked by the Royal Navy.

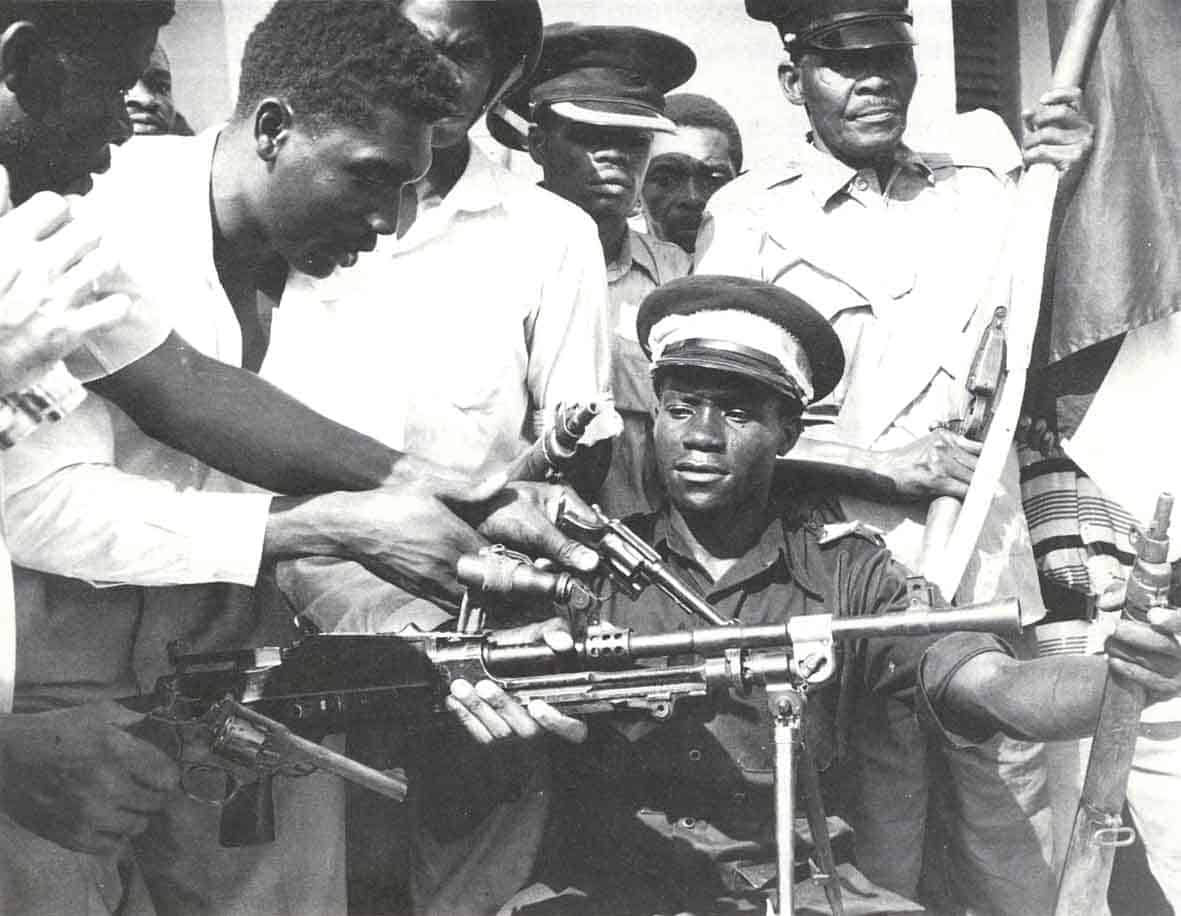

During that time, the continental Tanganyika was in the possession of Germany, and after the First World War, it belonged to the British. In the wake of the decolonization of Africa on December 10th, 1963, the British gave Zanzibar its independence. A month later, on January 12th, 1964, Commander John Okello, originally from Uganda, carried out coup d’éta, overthrew the sultan and ended the centuries-long Arab rule over the island. Okello’s troops, armed at first only with machetes and knives, overtook several police stations and a radio station after midnight. The insurgents had been given strict orders not to touch the Europeans, but the retribution on the Arabs and the Hindus was harsh. Sultan Jamshid bin Abdullah and his seven children escaped first to Oman and then Great Britain, where he lives to this day.

However, between 10,000 and 20,000 civilians of Arab and Hindu origin were not that lucky – they were massacred. Of course, different theories are still circulating about this event – one of them being that the British supplied weapons to Commander Okello and gave him a green light to massacre Arabs and Hindus. After the unification of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, Okello escaped the island. Seven years later, he was living in his native Uganda, where he was one of the advisers to the notorious dictator Idi Amin Dada. Last time he was seen alive was in the company of Amin in 1971, after which there was no mention of him. It is believed that Idi Amin ordered Okello to be killed because he considered him a threat.

I ask our driver whether schools in Zanzibar teach about the 1964 massacres. He answers with a “no”. The public, he says, is divided – some condemn the crimes, while others say that they were the result of justified anger. Sounds familiar?

The anger that he is talking about comes from “centuries of oppression” of the black African majority, mostly former slaves, by the ruling Arab and Hindu minority, which the British brought to Zanzibar, just like they did to other African colonies, to trade and do crafts. In the film ‘The Last King of Scotland’ we all saw what happened to the Ugandan economy when the crazed dictator Idi Amin Dada decided to expel all Hindus.

In any case, there is no museum or even a monument built in commemoration of this genocide. The video clip made by the Italian cameramen was sufficient for the genocide to be documented and remembered. A friend of mine who lives in Oman wrote to me how, even 55 years after the massacre of their fellow countrymen in Zanzibar in 1964, the memory of it was still painfully alive.

At the same time when the Sultan and the surviving Arabs and Hindus escaped Zanzibar, so did Bomi Bulsara and his family. Bomi was a member of the Zoroastrian nation called the Parsi who escaped Persia for India in the 5th century. Some of the Parsi people, together with certain South Asian nations, immigrated to Zanzibar in the 19th century. Bomi’s 18-year-old son, Farrokh will soon become world-famous under a different name – Freddie Mercury, the singer of the iconic band Queen, which fame was revisited last year thanks to the blockbuster ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. This is the island where one of the most important musicians of the 20th century was born and lived. However, there is only a plaque and several photographs in the window of his damp-ridden house in the centre of Stone Town, now belonging to the Tembo Hotel, where he was born, that remind us of that.

STINKYBAR, NOT ZANZIBAR

Many tourists consider this city, with magnificent churches, mosques, palaces, fortresses, romantic hotels, markets brimming with spices and narrow streets with gates and doors decorated with fine wood and stone ornaments, as one of the most beautiful in Africa and the world. It wasn’t always so.

“This town should be called Stinkybar, not Zanzibar”, wrote, in 1866, David Livingstone, the famous British explorer who lived in Stone Town at that time. Another British explorer, Richard Francis Burton, wrote in 1856 that Stone Town, as he approached it from the sea, looked like a canvas painting – with turquoise sea, snow-white mosques and palaces, and golden sunrises behind the roofs. However, when you disembarked, you were hit with the unbearable stench of dead animals and slaves thrown to the garbage on the city outskirts. Oriental beauty temporarily turned into an oriental nightmare. Other travelers from that time describe Stone Town as a city with a bunch of hungry slaves roaming the city streets, and a place where cholera, malaria and venereal diseases ruled.

140 years ago, in the place where today an Anglican church stands, there was a slave market. 50,000 slaves were dispatched to Zanzibar annually and after being sold at an auction, they were transported by their new owners across Africa and Asia. The slaves were captured mainly in the interior of East Africa, in the territories that today belong to Mozambique, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi… David Livingstone calculated that over 80,000 slaves died annually due to the poor transport conditions, before they even reached the market in Stone Town.

We have come to see an underground cell, in which, in the three days before an auction, the slaves were kept without food and water in ghastly hygienic conditions, with only one small slit for air. In the room on the left side, which spans not more than 20 square meters, about 50 male slaves were imprisoned, while up to 70 women and children were locked in the room on the right-hand side, of approximately the same size. I notice the horrified faces of my daughters, aged 12 and 14, while they are sitting on the stone beds in that cell and listening to a guide who tells them about the conditions in which the slaves were kept. A large number of photographs in the museum setting above the cell depict slaves who were freed by British troops but also the slave market showing dozens of people waiting to be sold.

Some of the slaves remained in Zanzibar to work on plantations. The 19th century chronicles mention that the conditions in which the slaves were kept were so severe that Zanzibar was the only place in the world that recorded no slave uprisings. Slave trade was abolished under a strong British pressure, but it was banned on the island only in 1897, although some of its forms, such as forced marriage, remained in place for decades to come. 67 years since the abolition of slavery, the centuries of pent-up hate exploded in Zanzibar in the January Revolution of 1964 that took thousands of innocent lives.

It is interesting to note that the victims and executioners in this case were both Muslims, since the black slaves converted to Islam during the centuries-long Arab rule. It becomes very clear, after only a few minutes of driving around, that you are, indeed, in a Muslim country. Women cover their heads, even small girls that are barely four years old, which is also when they start school that is both mandatory and free. Men are dressed just like their counterparts in Christian parts of Africa, without any external markings of a religion or belonging to an ethnic group.

FIRST AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF ARABIC WOMAN

The former Sultan’s Palace became the seat of the local government after the revolution when it was named People’s Palace. In 1994, it was transformed into a museum showcasing the centuries-old rule of the Oman sultans over the island. The museum is in a dilapidated state, reeking of mould, and suffering from poor maintenance. But it does have a certain tropical charm.

A special room in the museum is dedicated to Princess Salama bint Said, the youngest, 36th daughter of the Sultan of Zanzibar and Oman, Saeed Al-Busaidi. After the death of her father and mother (a slave from the Caucasus region), Princess Salama moved from the Palace to the city where she met the German merchant, Rudolph Heinrich Ruete. Salama and Rudolph were first neighbours and from her window, she could see dinner parties that Rudolph held at his house, as she later recalled in her autobiography. The two eventually fell in love, Salama got pregnant, and when her pregnancy could no longer be hidden, she had to leave Zanzibar on a British ship. The couple first lived in Aden, where the princess converted to Christianity and took the name Emily, married Rudolph and eventually moved to Hamburg, Germany, with him. Their first child died on their way to Germany. They later had another son and two daughters.

After Rudolph’s death, Salama faced financial woes. In 1886, she wrote the book “The Memoirs of the Arabian Princess of Zanzibar”, which, as the first autobiography written by an Arab woman, became an international literary hit. In addition to Germany, the book was also launched in Great Britain, Ireland and the United States. The English edition was re-printed in Zanzibar in 2018 and can be purchased at Sultan’s Palace. Although the book was written from a perspective of a Christian woman living in Europe, she defends slave trade, claiming that many properties in Zanzibar would be devastated without slave labour, and in one part of the book, she even endorses pure racism: “Whoever had any contact with blacks, whether in the United States, Brazil or Zanzibar, knows that despite their many qualities, they cannot be made to work otherwise than by force!”

She justifies the slave system in her homeland by the fact that “Muslims treat their slaves in a different way from Christians, almost as family members”. However, as we have seen, the European observers had a completely different view of this. Otto von Bismarck had plans to appoint Rudolph’s son as the Sultan of Zanzibar, so that, after the continental Tanganyika, he could rule the archipelago too. Nothing came off that, as the British beat him to it. Emily lived in Beirut from 1889 to 1914 and she died in 1924 in Jena, Germany, where she was also buried.

EYES THAT WATCHED DAVID LIVINGSTONE

Foreign tourists became interested in Zanzibar in the 1960s when hippies were searching for exotic tropical destinations like Goa, Kathmandu, or Zanzibar, and it has intensified since particularly after, in the year 2000, Stone Town was included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. In 2017, the number of tourists doubled compared to the previous year, amounting to 376,000. Interestingly, the Italians are the most numerous tourists in Zanzibar, although there is no special reason for that – Italy has its own sea (several of them), and it was never a colonial power south of Somalia. However, the Italians simply fell in love with Zanzibar and you can hear the Italian language spoken wherever you go. Pasta is served in almost all the restaurants. We enjoyed excellent seafood pizza and a great South African wine almost every night on the beach of our hotel, dining at the tables placed in wooden fishing boats that were shipwrecked on the shores of the Indian Ocean.

Restaurant ‘The Rock’ is probably the most photographed place on the island. It is located on a rock that was once used by local fishermen to dry their nets. It is managed, of course, by an Italian, and it serves excellent pasta made from local ingredients, from seafood to tropical fruit. Apart from enjoying sandy beaches, tourists engage in various activities related to the flora and fauna here – the giant Aldabra tortoises on the Prison Island, a gift from the British governor of Seychelles in 1919, have grown in number and there are 300 of them. The oldest is 194 years old and is old enough to have met David Livingstone. The Prison Island, as its name suggests, housed a prison long time ago and later it was quarantine for ship crew that sailed into Zanzibar. Another great attraction here is swimming and diving with dolphins in the far south of the island. There is also the unique Baobab Cafe, built next to a huge fallen baobab tree, in the place from which the boat that takes you to swimming with dolphins departs.

Good news is that, in 2006, Zanzibar banned import and use of plastic bags. This has somewhat improved the situation on an island that is quite unregulated, utilities-wise. The general impression is that, apart from luxury hotels, everything else in Zanzibar is quite neglected and left to decay in high humidity – houses, schools, government buildings, even mosques, palaces and museums. The Aga Khan Foundation has renovated several of the most important buildings in Stone Town, such as the House of Wonders. Nevertheless, if maintenance is not done regularly in the tropical climate, everything very quickly decays and turns grey. There is also an abundance of speed bumps which stop fast drivers in their tracks. They are necessary because, during our one-hour drive from the airport to the hotel, we counted at least a dozen village schools, all situated along the road.

Apart from the real gems of oriental architecture and art in Stone Town, we also came across parts of the town that reminded us of socialist residential blocks in East European towns. These are residential complexes that were built in the 1960s by the comrades from the German Democratic Republic (GDR). After 1964, the revolutionary government of Zanzibar nationalized all Arab and Indian properties, houses, buildings, plantations and factories and formed close relations with the USSR and other socialist states. Always agile, the GDR was, of course, at the helm of it. As it turned out, by some twisted historical irony, the Germans finally got to the islands, not with the help of Bismarck or Princess Salama, but in their Communist edition.

Rođen 27.7.1968. u Baču (Vojvodina, Srbija). Srednju školu završio u Bačkoj Palanci, Pravni fakultet studirao u Novom Sadu. Od 1990. radi kao novinar – u početku kao novosadski dopisnik beogradskih “Večernjih novosti”; zagrebačke “Arene”, sarajevskih “Naših dana”. Sarađuje i u magazinima “Vreme” i “Stav”.

1992. sa grupom studenata obnavlja izlaženje studentskog mesečnika “Index”. Posle dva broja sledi smena celokupne redakcije i pokretanje magazina “Nezavisi Index” koji će kasnije 1993. promeniti ime u “Svet” iz kojeg je nastala izdavačka kuća Color Press Grupa.

Danas na čelu Color Press Grupe najvećeg izdavača magazina u regionu sa kompanijama u svih 6 republika – 110 magazina, 25 internet portala i preko 80 konferencija i festivala godišnje.

U porfoliju kompanije pored domaćih (poput magazina “Lepota i zdravlje”, “Svet”, “Pošalji recept”, “Lekovito bilje” itd) nalaze se i brojni licencni brendovi: “The Economist”, “Hello!”, “Gloria”, “Story”, “Star”, “Lisa Moj stan”, “Hausbau”, “Brava Casa”, “Bravo”, “Alan Ford”, “Grazia”, “La Cucina Italiana”, “Auto Bild” i brojni drugi.