How a war far away, thousands of kilometres eastward from the Mediterranean, led to the birth of a vivid Russian colony on the island of Capri in the early 20th century

When I first came to Capri six years ago, we were driven by a taxi driver in an open-top car, bearing ads of the Capri wristwatches, from Marina Grande to the center of the city on the top of the island. We left a small bus station which had only three bus lines (to Marina Piccola, Anacapri and Marina Grande). I immediately noticed the poster with the caption “Russian Week at Capri”, hanging on the wall next to the large obituaries and I wanted to find out more about the link between this peaceful Mediterranean island and the cold, faraway Russia.

The 1904-1905 Russian-Japanese War, which generated great resistance among the intellectuals in Moscow and St. Petersburg, was credited with turning Capri into the “southernmost Russian island”. The first Russian to come here was the famous writer Maxim Gorky together with his mistress Maria Andreyevna. They arrived on the German ship “Princess Irene” in 1906 to the port of Naples from New York where the famous writer had been collecting money for the revolutionaries in Russia. There, in Naples, Gorky was planning where to live next since if he returned to Russia he would be either imprisoned or exiled to Siberia. The island of Capri was recommended to him, which due to its mild climate agreed with his health while the island’s rural environment was ideal for writing.

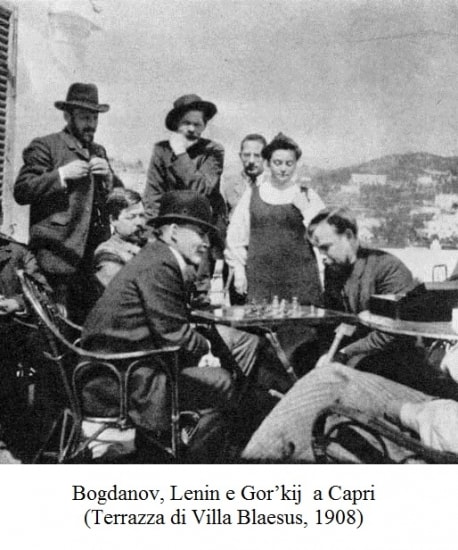

POLITICAL SCHOOL ON THE VILLA’S TERRACE

Although Gorky and Andreyevna planned to stay shortly on the island, they were so mesmerized by its beauty that they continued living on Capri for the next seven years. After Gorky, many other Russians started coming to the island, also opponents of the Tsar’s regime, the police repression and the huge differences between the social classes. The Villa Blaesus on Capri, where Gorky and his mistress were accommodated, soon after became the meeting place of many Russian writers, actors, philosophers, scientists, musicians and other intellectuals who were often photographed in the company of the great writer on the villa’s terrace, playing chess. These included Alexander Bogdanov, a physicist and science fiction writer, writers Anatoly Lunacharsky, Ivan Bunin and Leonid Andreev, philosopher Vladimir Alexandrovich Bazarov, tenor Fyodor Ivanovich Chaliapin and last but not least, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, the leader of the October Revolution. There was a real political school taking place at the terrace with lively discussions where they talked and dreamed about how the future Socialist society would look like.

Gorky was delighted with the island, he wrote a great deal of his work here, and once even said: “I feel intoxicated here although I haven’t even touched the wine!”. During his stay on Capri, he was visited by his lawful wife and their three children several times. Their stay was clouded in a strained silence, until the intolerance between the two women exploded and brought about the abrupt end to the visit.

In 1913, Tsar Nikolai generously pardoned his political opponents and in marking of the 300th anniversary of the Romanoff’s rule, he allowed Gorky to return to Russia in early 1914. Following the October Revolution and Lenin’s death, Gorky returned to Italy, but this time it was the mainland Italy, the town of Sorrento. Penniless and almost forgotten, as Solzhenitsyn later claimed, Gorky accepted Stalin’s offer to return to the USSR, and the news that “the famous writer left Mussolini’s fascist Italy and returned to his homeland” was broadcasted from the loud speakers of the Soviet propaganda machinery. So, the famed Gorky forever left the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea. However, the myth about the Russians who, in the early 20th century, brought intellectual charm to this idyllic Mediterranean island is alive to this day.

In the past years, I met a different kind of Russians on Capri – the so-called “winners of the transition” that arose from the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although far different from the intellectuals from the beginning of the 20th century, today’s Russians in Capri are still much more cultivated than those frequenting other luxurious Mediterranean ports, including those on Capri, in the early 1990s, throwing their money left and right and having worse manners and lesser education compared to their fellow countrymen who came before them a century earlier.

DEATH BECAUSE OF CAPRI

Another famous contemporary of Maxim Gorky, though from a completely different social class, was also a resident of this island. Alfred Krupp, one of the richest men of his time and an industrialist whose last name is still synonymous with steel, spent on Capri a few months every year. He stayed at the famous Quisisana Hotel, one of the oldest and most expensive hotels in Europe. Krupp had anchored two yachts – “Maya” and “The Puritan” – in the island’s marinas. However, his behavior on Capri was anything but Puritan. First, in the spring of 1902, the Naples-based newspaper, Mattino published an article about a wealthy German industrialist (without naming names) who spent summers on Capri, holding parties, mostly frequented by local young men. Soon, various social-democratic newspapers from Germany, started running the same stories, this time mentioning Krupp’s name, with the scandal echoing all around Europe. The stories centered on Krupp’s relationship with an 18-year-old local barber and musician, Adolfo Schiano. In October 1902, Krupp’s wife, Margaret, received an anonymous letter containing photographs of her husband’s orgies. She complained to a family friend, Kaiser Wilhelm, in an attempt to influence her husband and protect her reputation. However, the Kaiser ordered that the wife of his main supplier of cannon steel should be taken from the family home and placed in a mental hospital “in order to forever silence her”.

The social-democratic press was relentless in reporting about Krupp, culminating in Krupp’s suicide on 22nd November, 1902. At his funeral, the Kaiser directly accused the press of causing Krupp to commit the suicide. This version of “Death in Venice” ended in a much less poetic manner compared to the one in the Thomas Mann novel, written 10 years prior.

Today, the Hotel Villa Krupp is the only thing on Capri that is reminiscent of the King of Steel. The hotel is located in the place of the former villa where Maxim Gorky used to stay, on Via Krupp, which is a steep path that descends from the villa to Marina Piccola on the other side of the island, and was built in 1900 by Alfred Krupp. Here, in my opinion, lies one of the most beautiful beaches in the world.

THE EGYPTIAN KING’S FARUK DAYS OF EXILE

Apart from Krupp, many other famous people stayed in the aforementioned Quisisana Hotel, in which, they say, rooms are booked up to a year in advance, like Oscar Wilde, Sydney Sheldon, Tom Cruise, the US President Gerald Ford, Sting and Jean-Paul Sartre.

The exiled Egyptian King Faruk I also spent his days here, in a building that was built by the British doctor, George Sydney Clarke in 1841, originally as a sanatorium. Twenty years later, the building was transformed into a luxury hotel which it remains to this day, 157 years later.

“This place is not according to my taste”, said the British writer, Graham Greene when he first stepped onto the island. However, he did change his mind later, bought a small house in 1948 and returned to Capri every year after that, for 40 years. A long list of celebrities who lived and worked on Capri did not end with Gorky, Krupp and Greene. The island was also host to Grace Kelly, Audrey Hepburn, Giorgio Armani, Rudolf Nureyev, Sophia Loren and Ernest Hemingway. Of course, the first “celebrities” here were Roman emperors Augustus and Tiberius, with the latter one spending his last years at the Villa Jovis, on the top of the island.

When, five years ago, I visited Anacapri, the less-populated part of the island, I discovered another exciting biography related to Capri. Casa Rossa (The Red House), an unusual building in the centre of Anacapri, is linked to the American John Clay MacKowen, a confederate colonel, who, after the Union won the civil war, emigrated to “the good old Europe” and settled in Capri in 1870. The eccentric retired colonel lived with a local girl with whom he had a daughter, and because of his hot temperament and generosity he was very popular with the islanders. As an amateur, he dabbled in archeology and collected rare artifacts from around the world. MacKowen returned to Louisiana before his death in 1901 and his meticulous collection is now exhibited at Casa Rossa.

Rođen 27.7.1968. u Baču (Vojvodina, Srbija). Srednju školu završio u Bačkoj Palanci, Pravni fakultet studirao u Novom Sadu. Od 1990. radi kao novinar – u početku kao novosadski dopisnik beogradskih “Večernjih novosti”; zagrebačke “Arene”, sarajevskih “Naših dana”. Sarađuje i u magazinima “Vreme” i “Stav”.

1992. sa grupom studenata obnavlja izlaženje studentskog mesečnika “Index”. Posle dva broja sledi smena celokupne redakcije i pokretanje magazina “Nezavisi Index” koji će kasnije 1993. promeniti ime u “Svet” iz kojeg je nastala izdavačka kuća Color Press Grupa.

Danas na čelu Color Press Grupe najvećeg izdavača magazina u regionu sa kompanijama u svih 6 republika – 110 magazina, 25 internet portala i preko 80 konferencija i festivala godišnje.

U porfoliju kompanije pored domaćih (poput magazina “Lepota i zdravlje”, “Svet”, “Pošalji recept”, “Lekovito bilje” itd) nalaze se i brojni licencni brendovi: “The Economist”, “Hello!”, “Gloria”, “Story”, “Star”, “Lisa Moj stan”, “Hausbau”, “Brava Casa”, “Bravo”, “Alan Ford”, “Grazia”, “La Cucina Italiana”, “Auto Bild” i brojni drugi.